In my long overdue reading of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists, I'm encountering

some useful details that inform family history, and link the latter to more

general historical research.

One of my historical case studies (which I'd like

to develop further, archaeologically) is a terrace of houses within Derby.

|

| Looking towards the bottom of the terrace (which ended in a high wall), with the pathway to the railway (now closed) marked by rendered wall on left |

|

| Photos of the terrace, taken in 2005. (Original C19 buildings demolished and replaced by the red brick buildings in the centre of the photo and below, centre right) |

|

| Looking from midway down terrace, towards the junction, from which the first photo was taken |

This street (primarily of 'two-up-two-down' houses)

was built in the mid C19. The houses had front gardens and small back yards,

with a small brick-built (& white-washed) wash-house & coal-house, and WC

at right angle to the yard wall (facing that f the neighbouring property). By

the 1930s, the external walls of the houses had been rendered. The garden of

each house was usually separated from the next by a small fence or hedge. Every

few houses, an 'entry' provided access to the rear yard (this would give about

1 yd. extra space to the bedrooms of some houses. Backing on to both Derby gaol

(the perimeter wall forming the enclosing wall of the back yards to these

buildings), and with the (Great Northern) railway station & goods buildings

nearby, two possible sources of employment were open to the occupants - the

former until the early 30s (in 1933, the gaol housed a greyhound stadium, which had

(very noisy) - races every Wednesday and Saturday nights) & the latter

until the 60s.

|

| Front garden, most likely Easter, 1970-71 (apologies for poor quality. Copyright restrictions apply: All rights reserved. Image will be removed on request of interested parties) |

The front door opened onto a small (& from what

I remember, quite dark) room, measuring c. 8'-9' x 10' (all the measurements

are for the moment only approximate), with a fireplace (many with tiled surrounds

installed between the 30s & 50s - mostly later) door leading to the

kitchen.

The kitchen measured c. 8'-9' x 6-8', and had one

door leading to the stairs, and one leading to the back yard. Each had a

'Belfast' sink and cold tap, beneath a rear window overlooking the yard; by the

60s, most had a small hot water boiler on the wall nearby. The kitchens were

originally equipped with a cast iron cooking range, although many of these were

replaced between the 1930s & 50s, by enamelled ranges, although by the end

of the 60s, some had gas cookers. This room was just large enough for a small

table and cupboard, and a tin bath, when in use (I have a memory of one family

member taking a bath in front of the fire in their house in this terrace).

At the top of the stairs was a small landing (the

size of the width of the doors and their frames). One door led to a bedroom

above the kitchen; this had a small cupboard in the space above the stairs, and

a window overlooking the yard & gaol / greyhound stadium. Another door

opened onto the bedroom above the front room, which had a window overlooking

the front garden.

A local almshouse charity brought this and adjoining rows, to provide residencies for 'poor' people of Derby (necessarily those fitting within the 'deserving' category, at least ostensibly - although inter-generational occupation seems to be very common). (I've still to determine the date when this charity took charge of these buildings- which will probably be quite an easy job, but I haven't yet had time to follow this up). A report by the charity, dating to 1970, was until recently available online, but the link seems to have gone. It reads:

“ALMSHOUSES AND ALMSPEOPLE.

33. Saving for existing almspeople and

pensioners - Appointments of almspeople under this Scheme and application of

income under the last preceding clause hereof shall be made without prejudice

to the interests of the existing alrnspeople and pensioners of the Charity.

34. Almshouses - The almshouses belonging to

the Charity and the property heretofore occupied therewith and the almshouses

to be erected as aforesaid shall be appropriated and used for the residence of

almspeople in conformity with the provisions of this Scheme.

35. Qualifications of almspeople - (1) The

almspeople shall be poor persons of not less than 60 years of age who have

resided in the area of benefit for not less than five years next preceding the

time of appointment.

(2) If on the occasion of a vacancy there are

no applicants qualified as aforesaid suitable for appointment the Trustees may

appoint a person otherwise qualified as aforesaid who has resided in the County

Borough of Derby for not less than five years next preceding the time of

appointment to be an almsperson of the Charity.

37. Notice of vacancy. - No appointment of an

almsperson shall be made by the Trustees until a sufficient notice of an

existing vacancy specifying the qualifications required from candidates has

been published by advertisement or otherwise so as to give due publicity to the

intended appointment but it shall not be necessary to publish a notice if a

vacancy occurs within twelve calendar months after the last notice of a vacancy

has been published. Notices may be according to the form annexed hereto,

38. Applications. - All applications

for appointment shall be made in writing to the Trustees or their clerk in such

manner as the Trustees direct. Before appointing any applicant to be an

almsperson the Trustees shall require him or her to attend in person unless he

or she is physically disabled or the Trustees are of opinion that special

circumstances render this unnecessary. Every applicant must be prepared with

sufficient testimonials and other evidence of his or her qualification for

appointment.

39. Selection of almspeople. - Almspeople

shall be selected only after full investigation of the character and

circumstances of the applicants.

40. Appointments of almspeople. - Every

appointment of an almsperson shall be made by the Trustees at a special

meeting.

...

42. Absence from almshouses- The Trustees

shall require that any almsperson who desires to be absent from the almshouses

for a period of more than 24 hours shall notify the matron or the clerk of the

Trustees and that any almsperson who desires to be absent for more than seven

days at any one time or for more than 28 days in any one year shall obtain the

prior consent of the Trustees.

43. Rooms not to be let. - No almsperson

shall be permitted to let or part with the possession of the room or rooms

allotted to him or her or except with the special permission of the Trustees to

suffer any person to share the occupation of the same or of any part thereof.

...

RELIEF IN NEED.

47. Relief in need. - (1) The Trustees shall

apply income of the Charity applicable under the head of relief in need in

relieving either generally or individually persons resident in the area of

benefit who are in conditions of need, hardship or distress by making grants of

money or providing or paying for items, services or facilities (including

apprenticeship premiums) calculated to reduce the need, hardship or distress of

such persons.

(2) The Trustees may pay for such items,

services or facilities by way of donations or subscriptions to institutions or

organisations which provide or which undertake in return to provide such items,

services or facilities.

...

51 . Charity not to relieve public funds. -

The funds or , income of the Charity shall not be applied in relief of rates,

taxes or other public funds.

...

FORM OF NOTICE.

...Notice is given that a vacancy exists for

an almsperson of this Charity: Poor persons of not less, than 60 years of age

who have resided in the area...as in 1547, for not less than five years next

preceding the time of appointment are eligible- for appointment. In default of

suitable applicants qualified as aforesaid, persons otherwise qualified who

have resided elsewhere in the County Borough...for not less than five years

next preceding the time of appointment, may be appointed. - Application for

appointment must be made in writing to at on or before the 19 .

Every applicant must state his or her name,

address, age and occupation and must be prepared to produce sufficient

testimonials and other evidence of his or her qualification for appointment and

unless physically disabled to attend in person."

These

rules perhaps seem a little controlling, although in practice they don't seem

to have been applied with much force: at this date, I lived there with my

mother (her name appears in this document - at the time she was aged 26. Next

to her name, in the 'gross yearly income' column - i.e. from rent - is £52.65).

Background: demographic information from family history and census (names have been withheld, for the privacy of surviving members of the family)

The reason that I've selected this is due to the

availability of cartographic data in conjunction with both (family) oral

history, and my own memories of this street - so, getting dangerously close to

'auto-archaeology')

Although I was born (in the late 60s) on the

maternity wing of a local hospital, I came home to live in this street for

several years, until it was demolished; my mother had lived in another (at

different times, two) of the houses on the street, as had my grandmother,

great-grandmother, and great-great-grandmother: my maternal family occupied the

street for over 100 years; my uncle, aunt & cousins also lived in one

house, and a great aunt in another. Consequently, I both remember the

buildings, and have access to personal and social memories.

No.

|

Name

|

Relation to head of family

|

Condition as to marriage

|

Age last birthday

|

Profession or occupation

|

Employer, Worker, or own account

|

Where born

| ||

M F

| |||||||||

4

|

Emma T.

|

Head

|

Wid.

|

72

|

Derbys.

Derby

| ||||

Do.

|

Oscar A.

|

Adopted son

|

S

|

10

|

Do. Do.

| ||||

Do.

|

Joseph M.

|

Boarder

|

Widr.

|

65

|

Living on own means

|

Do. Do.

| |||

5

|

Joseph M.

|

Head

|

M.

|

49

|

Railway Lampman (lighter)

|

Worker

|

Northants.

Peterborough

| ||

Do.

|

Harriet do.

|

Wife

|

M.

|

45

|

Derbys.

Derby

| ||||

Do.

|

Margaret do.

|

Daur.

|

S.

|

25

|

Brushmaker

|

Worker

|

Do. Do.

| ||

Do.

|

Ethel do.

|

Daur.

|

S.

|

17

|

Cotton Seamer Hosr.

|

Worker

|

Do. Do.

| ||

1901 Census record of the houses occupied by the family. Harriet is daughter of Emma (& therefore Ethel's grandmother)

My great-grandmother (Ethel: born 1883, d. 1941)

lived in this terrace. As the census indicates (if it's not mixing the work of

Ethel with that of her sister), she worked as a cotton seamer. (This was perhaps

in a nearby hosiery factory - there were several mills in the parish, one

photographed here - although the

machines seem to have produced seamless stockings, and it is

noted that a small number of people

continued home working into the 20th century.)

She married March 1913 (to a man several years her junior) & had 3 children - one of whom (born in the 20s) died in an road accident, aged 8. Her husband (a railway worker) abandoned her when the children were small, so she was forced to bring them up alone: she is listed in a local trade directory as 'char woman', but I'm informed by my mother that she was an accomplished seamstress (this was Ethel's mother's trade - reputedly for the adjacent prison), taking on work for Harrods; she is also said to have created window displays for the store. Either Ethel or her mother went to art school - unusual for women from this background at the time. My grandmother told me that her mother's middle name (Alvina) was given to remember the 'foreign' nurse who had cared for a factory-owning antecedent (see below) on his deathbed. I'm finding it quite tricky to find any evidence for these beliefs (I could conjecture that this could be explained by possible indicators of illegitimacy within earlier generations that I've encountered in the records)

|

In the garden of the terraced house. On the left:

probably my grandmother’s sister; on the right: the youngest sister (who died,

aged 8)

|

Ethel's older sister seemed to have had a better

life (living nearby, but in a larger house, trading antiques) (I speculate as

to the role that the birth of my grandmother only 4 months after her mother's

marriage upon her deprivation in comparison to her older sister) - there was

some small capital on he family, according to my grandmother, derived from

links to a local mill-owner's family. (Again, I can only speculate that, if

true, such ties were out of wedlock, as I've yet to find any indication of this

in the census or other records.)

I'm informed that Ethel regularly scrubbed the

steps of her more affluent sister; Ethel's relatively young death was reputedly

as a result of kidney disease (which seems to be related to her hard life),

although I'm also informed that she met her end dramatically, by falling

downstairs (as she couldn't see very well?) & breaking her neck or bleeding

to death.

With regard to material culture, I have a few

artefacts that connect with the past: on my marriage in the late 80s, I was

given (by my grandmother) a fragment of lace from 'a hundred year old wedding

dress', which I believe was that of my great-great-grandmother Harriet, and

which (if I'm remembering correctly) my grandmother carried on her own wedding

day (as did I), as 'something old':

|

| (Copyright restrictions apply: All rights reserved. Image will be removed on request of interested parties) |

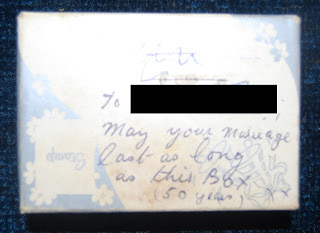

This was given to me in a box from the time of my

grandmother's wedding (1938), which had held a piece of wedding cake:

|

| (Copyright restrictions apply: All rights reserved. Image will be removed on request of interested parties) |

I am told that my great grandmother had some 'fine'

antique furniture, which was sadly destroyed in the floods of the 30s, as

recorded here, in the Derby Evening Telegraph, dated Monday 23 May, 1932:

|

| (Copyright restrictions apply: All rights reserved. Image will be removed on request of interested parties) |

The column to the left of the front page is headed Human Stories of Derby's Great Flood. The second section mentions the damage done to the terrace:

(Copyright restrictions apply: All rights reserved. Image will be removed on request of interested parties. Redaction may be removed in due course)

I was informed by my grandmother that this was one

of the few remaining objects from her mother's collection (a mahogany mirror

and drawer, that appears to date to the late Victorian - Edwardian period), presumably

salvaged thanks to its location on the wall above the flood level. It is now in

my possession, but has deteriorated over the years:

The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists and the seamstress at home in the early 20th century

Bearing in mind my great-grandmother's history, the 's mention of

home-working for women (particularly for seamstresses) in RTP is of particular

interest & relevance:

At first they had employed her exclusively on the cheapest kind of blouses-those that were paid for at the rate of two shillings a dozen, but they did not give her many of that sort now. She did the work so neatly that they kept her busy on the better qualities, which did not pay her so well, because although she was paid more per dozen, there was a great deal more work in them than in the cheaper kinds. Once she had a very special one to make, for which she was paid six shillings; but it took her four and a half days--working early and late--to do it. The lady who bought this blouse was told that it came from Paris, and paid three guineas for it. But of course Mrs Linden knew nothing of that, and even if she had known, it would have made no difference to her. Most of the money she earned went to pay the rent, and sometimes there was only two or three shillings left to buy food for all of them: sometimes not even so much, because although she had Plenty of Work she was not always able to do it. There were times when the strain of working the machine was unendurable: her shoulders ached, her arms became cramped, and her eyes pained so that it was impossible to continue. Then for a change she would leave the sewing and do some housework."

(2005 OUP edn., p. 325)

The descriptions of this character's work at home (a young widowed woman with a

small young family) is consequently interesting with regard to the experiences

of my grandmother & great grandmother, and their conditions, and vice

verse.

However, in examining my family's past, a number of

pieces of evidence come to light that might to some contradict social

categorisations, and the apparent quality of life for 'the poor'; they

certainly demonstrate the complexities and impact of social relationships upon

material culture. There are occasional moments during which my grandmother was

placed in better circumstances, which are closely related to the dynamics of

the extended family: she appears to have benefited from spending much time with

her maternal aunt, which gave her an interest in (and access to) better clothes

and a social life (she very much enjoyed dancing). For instance, I have a

studio photograph (on a postcard that bears the name of the Pollard Graham

studio, Friar Gate, Derby, which is very similar to an example

dating to 1920) of her as a girl that seems incompatible with

poverty (she is wearing a velvet dress, which might be assumed to be a fabric

for the wealthy); the cost of a studio photo seems out of the reach of a family

headed by a 'char woman' (again, sorry for the quality of this photo).

|

However, the exact circumstances of this moment in

time are lost to us - but it is of interest, as it doesn't seem representative

of life within the terrace, as either described, or represented by the material

remains. In considering the clothes, we may see a possible explanation within RTP, where we read

that the son of the (poor) main character was made a velvet suit by his mother,

from an old dress of her own. Ethel's and her mother's skills as seamstresses

(and employment of the former in making what would have been expensive clothes,

using fine materials) perhaps explains the origin of the clothes within this

photo. But it is as likely that my grandmother borrowed these clothes, or was

given them as 'hand-me-downs', perhaps from the more wealthy aunt.

This highlights the flexible & changing meaning and social significance of objects (in this case, fabrics), and demonstrates how we must take care to look beyond the context being studied - how we may do this archaeologically is another question, for another day (although it is suggested here that multi-scalar analysis is essential). Social networks are clearly very relevant when attempting to understand life (whether of the 'lower classes', as they were often called, or of those belonging to 'higher' socio-economic groups). Moments of 'good luck' (e.g. the receipt of small inheritances or gifts, or winnings from gambling or, e.g. school prizes) might also cloud the picture. An example comes from my grandfather's life: I'm informed by his sister that, when at school, he won a suit as a prize in a calligraphy competition.

The author of RTP, Tressell (Noonan), states that he draws upon fact for his novel; it is suggested that he used both his own experiences, those of others, and dramatised data obtained from a variety of sources. Therefore, this extract may reflect the conditions experienced by women just before the First World War (at the time of my great-grandmother's marriage and the birth of my grandmother), but not necessarily record the actual experiences of a known family. However, the novel was popular, at least in part, because it did accurately describe (and for some, expose) life for the poor at this time.

The census information reveals what to us may seem unusual: for instance, 'living on own means' often occurs in the records related to even the poorest houses. It also demonstrates that not everyone had large families at the time - a common assumption. The reason why my great-grandmother married is arguably self-evident given the social context and its moral codes, although I have yet to find the reasons behind her relatively late marriage (marriages during this period were, on average, much later than before or after, see Thompson, Paul 1992 The Edwardians. The remaking of British society, 31, 33, but 29 seems particularly late). One thing that is clear from an examination of surviving artefacts in conjunction with texts (including literature - such as the RTP - and journalism - such as the books of Ada Chesterton: see earlier posts) is that the inhabitants of almshouses were not often the destitute with no other recourse, but were more frequently those with access to at least a few shillings a week to pay rent - however meagre in comparison to the rents commanded by private landlords. The almshouse occupant seems to have led a comparatively stable life, compared to many (comparisons can perhaps be made to those occupying local authority housing, although rents in this sector were commonly higher than those of almshouses).

It may seem to be stating the obvious to make these points, but they highlight the need to investigate social structures and institutional practices, so that we might explore - as fully as possible - seemingly 'out of place' objects and behaviour. Though we may rarely be certain of the causes of apparent contradictions within the historical record, these moments of contrast (that can coexist with and become integrated within 'normal' life over a long period of time) enable us to gain a more nuanced understanding of the past. In particular, they hold the potential to consider attempts at transforming social circumstances and identities (such as 'class'), and to question (supposedly?) aspirational practices.

No comments:

Post a Comment