Much of my research into the negotiation of social status

and identities within eC20 domestic contexts is concerned with relationships

between domestic staff and their employers. In particular, it is evident that

spatial organisation had a primary role in the construction of difference

between 'master' or 'mistress' and 'servant during the Edwardian period. Within

the relatively (financially) comfortable middle-class home at this time,

construction of houses over three or four stories enabled strict divisions

between employer and employee to be observed. Whilst the ground and first floor

rooms were the domain of the householder, their family, and guests (though

children's nurseries were sometimes located on second floors), the highest

(usually attic bedrooms) and lowest

(frequently basement workspace) rooms were commonly the domain of

domestic staff - who were physically as well as socially separated and distant

from their supposed 'betters'.

My main question has so far been, considering these clear

socio-spatial boundariesof the pre-war (WWI) era (further defined by the green

'baize door' - which separated the worlds of servant and 'master' (and / or

'mistress'), how were these differences enacted within 1920s-30s households

(increasingly within sub-urban, rather than urban, contexts) that either 'kept'

live-in domestic staff (an decreasingly common situation), or engaged 'daily'

domestic staff, considering the changes made to domestic buildings during the

interwar period?

Although (for many reasons) fewer 'live-in' staff were

engaged, daily 'help' was still deemed as necessary for many households headed

by 'professionals'. With the expansion of the Middle Classes during the 1930s, and the spread of upwardly mobile families into newly developed suburban

estates, many women from families that had perhaps previously engaged at least

a 'maid-of-all-works' undertook domestic chores themselves, with the aid of new

technologies (principally aided by the development of electricity services: see

fig. 1; but also with innovations such as the thermostatically controlled gas

oven). Household chores were rebranded under the heading of domestic 'science'

for the middle class 'house-wife', becoming a more acceptable facet of suburban

life for the 'comfortably off'.

| ||

| Fig. 1. 1930s enamelled (with wooden handle) electric steam iron (© K. Jarrett 2012) |

(All objects are from Derventio Archaeology's teaching collection.)

Dress was also a principal mechanism for distinguishing

between the powerful and the subservient, uniforms going some way to conceal

the individuality of domestic staff. Some items of domestic service uniform

are shown here:

|

| Victorian or Edwardian cotton half-apron (fig. 2, above) and pinafore apron (fig. 3, below) (© K. Jarrett 2012) |

According to the testimonies of several women in service

at this time (e.g. Powell ), the cap (especially) was seen as a symbol of

servitude. Here are several aprons, collars, and cuffs, the colour of which

suggest may have been worn with either the morning print / patterned dress (figs. 3 and 4), or

an afternoon plain dress of mid - dark brown (see fig. 5), though black was the usual

colour (figs. 6 and 7)

|

| Fig. 5 Organza pinafore apron, collar and head-dress, with brown stripe (as with the black dress below, this type of uniform was also worn within a restaurant or cafe) (© K. Jarrett 2012) |

An added mechanism for social tension were the (often despised) uniforms; the caps in particular seemed to have been associated with opression. Servants

entering into the profession usually had to provide their own - frequently at

great cost. Although there were usually sufficient jobs available for those willing to work in domestic service, this cost (for girls and women, who were usually, but

not inevitably, drawn from the working-class), often required substantial financial sacrifice for families, primarily because their meagre wages were usually essential to the survival of the family at home. But here (figs. 7 and 8 ), we can see other

routes by which female servants

might obtain her uniform.

However, once in service, it had become

traditional practice for wealthier employers to provide

female servants with sufficient fabric to make a new uniform dress for the

following year, as a Christmas bonus. Servants were often given rooms for with few modern facilities. For example, even if much of the house was supplied with electricity, the servants' rooms often had to rely on candles; and even if equipped with an indoor toilet and bath, servants were often not permitted to use them, and had to rely on chamber pot and wash-stand.

Much of the mobility of women witnessed within census

records relates to domestic service: for example, my own great-grandmother

appears to have moved from the West Country to the West Midlands, and on to

Derby (where she met my great-grandfather - a railway worker), where it is

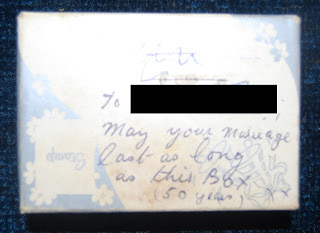

apparent that she became a nursery nurse at the turn of the 20th century for a well-known cricketer, at the propoerty in Friargate that is now Pickfords Museum. Even if having accumulated a number of possessions (of course modern consumerism is very different to the early 20th century, and very few categorised as working-class had many possession), this travel (usually unaccompanied, and often over long train journeys) limited what the employee might take with them to their new post; this would have had to include the various uniforms (as seen above). Perhaps the

most ubiquitous possession was

the trunk or 'box' (see fig. 9). This small but durable container (commonly made

of metal) would hold the bare necessities of belongings for servants in the positions

of employment - and even empty and often made of relatively light-weight tin, these containers are quite heavy.

|

| Fig. 9. Steel trunk (with mid-buff grained-effect painted decoration), of the size and type used by domstic employees to contain belongings whilst in service (© K. Jarrett 2012) |

Pehaps the most obvious objects that epitomised the relationship between employer and employee are the servant call-button ('bell') (figs. 10 and 11), call-box (fig. 12 and 13), and bell (fig. 14 and 5) - the usual route by which the servant was called for by their 'master' or 'mistress'.

| ||

| Fig. 10. Hard-wood (mahogany?) and ivory (or 'ivorine') electric call-button (back, fig. 11, below) (© K. Jarrett 2012) |

|

| Fig. 12. Early 20th century servant call-box (above); interior, below (fig. 13.) (© K. Jarrett 2012) |

|

| Fig. 14. Early 20th century brass and hard-wood call-bell; interior, below (fig. 15) (© K. Jarrett 2012) |

I am particularly interested in in situ examples (if anyone still has any examples within their own homes, please contact me!). My study of Building C was influenced by the example shown below (figs. 16-18).

| ||

| Fig. 16 Servant button in living room of Building C, c. 1930 (© K. Jarrett 2012) |

|

| Fig. 17. Servant button in dining room of Building C, c. 1930 (© K. Jarrett 2012) |

|

| Fig. 18. Servant call-box in kitchen of of Building C, c. 1930 (© K. Jarrett 2012) |

A building report of Building C, putting these objects in context, is available here. A future post will highlight some of the written sources available on this topic...